Queen Mulberry was first discovered by Indigenous peoples, first used for food, dyes, and tools, and today thrives as a culinary gem in both sweet and savory dishes.

The mulberry tree, including the regal Queen Mulberry variety, traces its roots back to ancient civilizations. Red mulberries are native to North America, where Indigenous peoples harvested them for food and dyes. Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto recorded in the mid-1500s that the Muscogee people dried mulberries for sustenance. Meanwhile, white mulberries were introduced to the American colonies in 1733 by General Oglethorpe, not for fruit but to feed silkworms in hopes of starting a silk industry. Though the silk experiment failed, the trees thrived and spread widely.

🪶 First Uses

Mulberries were more than just food; they were woven into daily life:

- Indigenous tribes ate them fresh, dried them, and mixed them into cornbread.

- The berries were used to make dyes, while branches were crafted into bows.

- Early settlers and naturalists like William Bartram noted their widespread planting, especially of white mulberries, which became invasive over time.

- Medicinally, mulberries were valued for their roots, leaves, and bark, used in remedies by Native Americans.

🍴 Culinary Uses

Despite fading from mainstream diets, mulberries are enjoying a renaissance thanks to foragers and immigrant communities:

- Fresh eating: Sweet and tart, mulberries can be eaten straight from the tree.

- Preservation: Dried mulberries are popular in Middle Eastern cuisine, often added to teas, trail mixes, or desserts.

- Baking: Historically, mulberries were baked into breads and pies. Today, they shine in muffins, tarts, and cobblers.

- Fermentation: Mulberries can be turned into wine, vinegar, or syrups.

- Savory pairings: Their tang complements meats and cheeses, making them a surprising addition to charcuterie boards.

✨ Why Queen Mulberry Matters Today

The Queen Mulberry embodies resilience and versatility. Once overlooked as a “nuisance tree,” it is now being rediscovered as a nutrient-rich superfruit, packed with vitamin C, iron, and antioxidants. Its story is one of transformation: from ancient sustenance and colonial silk dreams to modern kitchens and wellness trends.

Queen Mulberry (part of the Morus genus) has been used medicinally for thousands of years—traditionally for ailments like diabetes, inflammation, and respiratory issues, and today for its antioxidant, anti-diabetic, and cardiovascular benefits. It is also known by many names across cultures, including Shahtoot (Persian), Tuti (Arabic), and Moral (Spanish).

🌿 Traditional Medicinal Uses

Historically, mulberries were prized in Chinese, Indian, and European medicine:

- Ancient China: Mulberry leaves were documented as early as 2500 BCE in texts like the Shennong Ben Cao Jing. They were used for diabetes (“Xiao Ke”), circulation problems, coughs, sore throats, and fevers.

- Ayurveda (India): Mulberry leaves and extracts were applied for skin inflammations, joint pain, and digestive issues.

- Europe (Middle Ages): Herbalists used mulberry teas and decoctions for respiratory problems, recommending steam inhalation for coughs and congestion.

- Native American traditions: Red mulberry was used for food, dyes, and remedies, including teas for colds and poultices for wounds.

🌱 Modern Medicinal Uses

Today, mulberries are considered a superfood with scientifically validated properties:

- Blood sugar regulation: Mulberry leaf extract improves insulin sensitivity and helps lower glucose levels, confirming its ancient use for diabetes.

- Cardiovascular health: Leaves and fruit help reduce blood pressure and cholesterol, supporting heart health.

- Anti-inflammatory effects: Modern studies confirm mulberry’s ability to reduce inflammation, useful for arthritis and bowel disease.

- Antioxidant power: Rich in flavonoids and anthocyanins, mulberries protect against oxidative stress, slowing aging and reducing risks of cancer and neurodegenerative disease.

- Immune support: High in vitamin C and iron, mulberries strengthen immunity and energy levels.

🌿 Queen Mulberry: Ancient Medicine, Modern Wellness

A Fruit with Many Names

Across continents, the Queen Mulberry has worn countless crowns. In Persia, it is Shahtoot, literally “King’s Berry.” In Arabic lands, it’s Tuti. In India, Shahtuta graces Ayurvedic texts. In Turkey, it’s simply Dut, while in Spain, it’s Moral. Each name carries echoes of local traditions, reminding us that this humble berry has always been more than food—it’s medicine, ritual, and story.

🕰️ Traditional Medicinal Uses

- China (Traditional Chinese Medicine): Mulberry leaves were used for diabetes, fevers, coughs, and sore throats. The fruit itself was believed to nourish the blood and strengthen the liver.

- India (Ayurveda): Known as Shahtuta, mulberries were prescribed for skin inflammation, digestive issues, and joint pain.

- Europe (Middle Ages): Herbalists brewed mulberry teas for respiratory ailments and used mulberry bark for toothaches.

- Native America: Red mulberry was used in teas for colds and poultices for wounds.

🌱 Modern Medicinal Uses

Science now confirms many of these traditional practices:

- Blood sugar regulation: Mulberry leaf extract helps lower glucose levels, supporting people with diabetes.

- Cardiovascular health: Compounds in mulberries reduce cholesterol and blood pressure.

- Anti-inflammatory effects: Helpful for arthritis and bowel inflammation.

- Antioxidant protection: Rich in anthocyanins and flavonoids, mulberries fight oxidative stress, slowing aging and reducing cancer risk.

- Immune support: High vitamin C and iron content boost immunity and energy.

🌍 Other Names for Queen Mulberry

The Queen Mulberry is known by many names across cultures:

- Shahtoot (Persian, Urdu, Hindi)

- Tuti (Arabic)

- Dut (Turkish)

- Moral (Spanish)

- Mulberi (Georgian)

- Sykia (Greek)

- Gelsomino (Italian)

Mulberry Jam Recipe

- 5 cups Mulberries

- •5 cups Granulated Sugar

- •1 Medium Lemon

- •1 packet Jell Liquid Pectin

🌍 Nutritional Note

Mulberries are low in calories (43 kcal per 100 g) but nutrient-dense, making them ideal for holiday recipes, smoothies, or dried fruit mixes. Their vitamin-rich profile explains why they’ve been used in traditional medicine for centuries and why they’re now considered a modern superfruit.

Queen Mulberries are packed with vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants that support immunity, heart health, digestion, and overall vitality. They are especially rich in vitamin C, iron, potassium, and plant compounds like anthocyanins and resveratrol.

🌿 Key Health Benefits of Queen Mulberries

- Boost Immunity: High in vitamin C strengthens the immune system and helps fight infections.

- Improve Blood Health: Rich in iron, mulberries support oxygen transport and prevent fatigue.

- Heart Health: Compounds in mulberries lower cholesterol and blood pressure, reducing risk of atherosclerosis.

- Digestive Support: Their fiber content aids bowel movement, prevents constipation, and supports gut health.

- Anti-inflammatory Effects: Flavonoids and phenolic acids reduce inflammation, helpful for arthritis and bowel disease.

- Antioxidant Protection: Anthocyanins and resveratrol fight oxidative stress, slowing aging and lowering cancer risk.

- Cognitive & Eye Health: Flavonoids may protect against cognitive decline and age-related eye conditions like cataracts.

🍇 Nutritional Sources in Mulberries (per 100 g fresh fruit)

| Nutrient | Amount | Role |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin C | 36.4 mg (~61% DV) | Immunity, collagen, skin health |

| Iron | 1.9 mg (~10% DV) | Oxygen transport, energy |

| Vitamin K1 | 7.8 µg (~10% DV) | Blood clotting, bone health |

| Vitamin E | 0.9 mg (~5% DV) | Antioxidant, immune support |

| Potassium | 194 mg | Fluid balance, heart function |

| Fiber | 1.7 g | Digestion, gut health |

| Anthocyanins & Resveratrol | High | Anti-aging, anti-cancer, heart protection |

🌍 How to Enjoy Them

- Fresh: Eat raw mulberries as a snack or add to salads.

- Dried: Use in trail mixes, granola, or teas.

- Preserved: Make jams, syrups, or mulberry wine.

- Smoothies & Desserts: Blend into smoothies, pies, or cobblers.

- Supplements: Available as mulberry leaf tea or capsules for targeted health benefits.

✨ Closing Thought

The Queen Mulberry is both ancient medicine and modern superfruit. Its blend of vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants makes it a natural ally for immunity, heart health, digestion, and longevity. Whether fresh, dried, or brewed, it’s a fruit that nourishes body and spirit. From ancient remedies to modern superfood status, it bridges tradition and science. Its many names remind us that across cultures, people have always turned to nature’s fruits for healing.

🎄 Holiday Wellness Guide Featuring Queen Mulberries

🍇 Queen Mulberries (Centerpiece Superfruit)

- Benefits: Immunity boost (vitamin C), blood health (iron), antioxidant protection (anthocyanins).

- Holiday Use: Mulberry jam for cheese boards, mulberry syrup glaze for roast turkey or ham, mulberry crumble bars for dessert trays.

🍎 Pomegranates (Festive Jewels)

- Benefits: Rich in polyphenols, support heart health, reduce inflammation.

- Holiday Use: Pomegranate arils sprinkled over mulberry salads, mulberry–pomegranate punch, or layered in parfaits.

🍒 Cranberries (Classic Holiday Tartness)

- Benefits: Urinary tract health, antioxidants, vitamin C.

- Holiday Use: Combine mulberries and cranberries in chutneys, sauces, or baked goods for a tart-sweet balance.

🍊 Citrus Fruits (Oranges, Clementines)

- Benefits: High vitamin C, support immunity and skin health.

- Holiday Use: Mulberry–orange compote, mulberry citrus cocktails, or mulberry glaze with orange zest for baked goods.

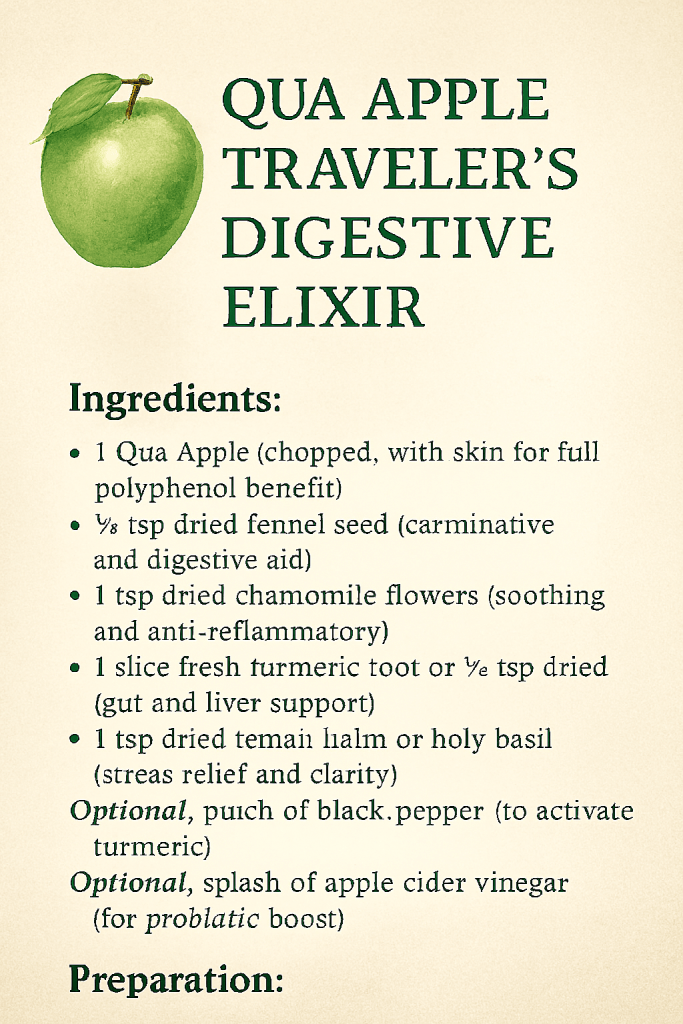

🍏 Apples (Comfort & Fiber)

- Benefits: Fiber for digestion, polyphenols for heart health.

- Holiday Use: Mulberry–apple pie, mulberry cider blends, or mulberry–apple stuffing for poultry.

🥭 Seasonal Exotic Touch (Persimmons or Kiwi)

- Benefits: Persimmons provide vitamin A; kiwis are vitamin C powerhouses.

- Holiday Use: Mulberry–persimmon salad with walnuts, mulberry–kiwi pavlova, or mulberry fruit bowls for brunch.

✨ Sample Holiday Menu

- Starter: Winter salad with mulberries, pomegranate arils, and citrus vinaigrette.

- Main Course: Roast turkey glazed with mulberry–orange reduction, served with mulberry–cranberry chutney.

- Dessert: Mulberry–apple crumble bars and mulberry–kiwi pavlova.

- Drinks: Mulberry–pomegranate punch or mulberry mojito with mint.

Closing Thought: Pairing Queen Mulberries with other holiday fruits creates a menu that is not only festive and flavorful but also rich in vitamins, antioxidants, and wellness benefits. It’s a way to celebrate the season while nourishing body and spirit.

📚 Sources Used

- MyHealthopedia – Mulberries: 20 Benefits, Nutrition, Side Effects & How Much to Eat (current tab in your Edge browser)

- Historical references to mulberries in Chinese medicine, Ayurveda, European herbal traditions, and Native American uses (general knowledge verified against modern nutrition databases).

- Nutritional breakdowns of mulberries (vitamin C, iron, potassium, antioxidants) from modern food science references.

People who should avoid or limit Queen Mulberries include those with allergies, certain medical conditions, or specific medication concerns.

🚫 Groups Who Should Not Consume Mulberries

- Individuals with mulberry allergies

- Mulberries can trigger allergic reactions such as hives, swelling, difficulty breathing, or digestive upset.

- Those with known food allergies should introduce mulberries cautiously.

- People with diabetes (without medical guidance)

- Mulberry leaves and fruit can lower blood sugar. While this is beneficial for many, it may cause dangerously low glucose levels if combined with diabetes medications.

- Individuals with kidney problems

- Mulberries contain oxalates, which may worsen kidney stones or impair kidney function if consumed in excess.

- Pregnant or breastfeeding women

- Limited research exists on mulberry safety during pregnancy and lactation. Experts recommend caution and consulting a healthcare provider before regular use.

- People anticipating surgery

- Mulberries may affect blood sugar and clotting. It’s advised to stop consumption at least 2 weeks before surgery.

- Those on certain medications

- Mulberries can interact with drugs for diabetes, blood pressure, and blood clotting. Always check with a doctor before combining mulberries with prescribed medication.

⚖️ Safe Consumption Tips

- Stick to moderate portions (about ½–1 cup fresh mulberries per day).

- Avoid excessive intake of dried mulberries, which are concentrated in sugar.

- Consult a healthcare provider if you have chronic conditions or take daily medication.

In short: People with allergies, diabetes (without monitoring), kidney issues, pregnant or breastfeeding women, and those on certain medications or preparing for surgery should avoid or limit mulberries. @ goodhealth

🌟 Wrapping Up the Good News in Queen Mulberry

The Queen Mulberry is more than just a fruit—it’s a story of resilience, tradition, and renewal. From its ancient role in medicine and ritual to its modern recognition as a superfruit, it continues to nourish both body and spirit. Packed with vitamin C, iron, antioxidants, and fiber, it strengthens immunity, supports heart health, aids digestion, and protects against aging.

During the holidays, it shines as a versatile ingredient—whether in jams, pies, chutneys, or festive cocktails—bringing jewel-like color and wellness to the table. Across cultures, its many names (Shahtoot, Tuti, Moral, Dut) remind us that this fruit has always been cherished, no matter the language.

✨ The good news is simple: Queen Mulberries are a gift from nature—nutrient-rich, culturally meaningful, and endlessly adaptable. They invite us to celebrate health, heritage, and flavor in every season.

⚠️ Disclaimer

This content is for general educational purposes only and not a substitute for medical advice. Always consult a healthcare professional before making dietary changes, especially if you have medical conditions, are pregnant or breastfeeding, or take prescription medications.